Michael J Dore was 14 when he first sensed that he was not like the other teenagers attending his all-boy school in London. While many of the other students would discuss the girls they hoped to kiss at the weekend, or cluster around pornographic magazines, Dore felt nothing of the blossoming, unfamiliar interest in their bodies.

“I thought I might be a late bloomer or maybe gay,” he says. Neither conclusion felt quite right, however, when it came to describing the utter absence of sexual or romantic attraction that Dore felt – or rather, did not feel. “Everyone has certain people they are not sexually attracted to. For me, everyone falls into this category.” A year later, at 15, Dore invented a term to describe himself: ‘asexual’.

At the time of Dore’s revelation in the mid-1990s, there was no asexual ‘community’ comparable to that of the burgeoning LGBT communities. There were no books on asexuality in the library, and only a meagre handful of lightly probing studies had been published in academia, variously exploring cases of worms, rodents and sheep that demonstrated no attraction to either sex.

These edge cases were labelled, in the literature, as ‘duds’. While researchers were beginning to circle on the idea that some humans went through life without ever experiencing sexual attraction, a more formal and less derogatory label was yet to be coined.

“I invented the term for myself independently – or at least others did on my behalf,” says Dore, now 33, who works as a mathematician in London. “Since then I’ve discovered that many people actually invent the term for themselves. They may have heard the term in biology classes – albeit with a completely different meaning of course, that leads to the inevitable jokes about being able to split like amoebae. It just seemed like a suitable term to pick up and use.”

It wasn’t until 2004, when the Canadian academic Anthony Bogaert, published the paper ‘Asexuality: Prevalence and associated factors in a national probability sample’ that the idea that a proportion of the population may experience no sexual attraction began to spread. Bogaert’s study, which used data collected in the 1990s from 18,000 British people, argued that around 1% of the population are asexual. Of that number, about 70% are women. The study suggested that there might be almost as many asexual people as there are gay individuals. Yet, despite the evidence, far fewer people identify as asexual as gay or bisexual.

This reticence is understandable not only in the context of history, with its grim persecution of those who do not fit the dominant models of living, but also of art, entertainment and literature, with their lingering focus on sexual longing.

In Euripides’ play, Medea, the Ancient Greek playwright wrote that, if one’s sexual life is good, “you think you have everything”. But if things are out of place in that area “you will consider your best and truest interests most hateful”. The idea that a person’s sex life defines their health and happiness persisted through the dark ages, the enlightenment and even the sexual revolution of the 1960s. In 1942, for example, Philip Wylie wrote that the sex instinct is “one of the three or four prime movers of all that we do and are and dream”.

The inference is, then, that a person devoid of sexual appetite is also devoid of dreams, of action, perhaps even of being. A 2002 article published in an annual magazine from the National Religious Vocation Conference in the US made the viewpoint explicit. ‘What do you call a person who is asexual?’ posed the article’s author. “Answer: Not a person. Asexual people do not exist. Sexuality is a gift from God and thus a fundamental part of our human identity.”

Coyness around asexuality is, then, understandable. A recent study from researchers at Yale University asked 169 self-identified asexual people to write an open-ended account of the development of their asexual identity and the disclosure of that identity to others. In many cases, the people interviewed described their revelations being met by friends and family with disbelief. One respondent was told: “You’re not a tree.” Another that it was “just a phase” and that they’d feel differently once they met the “right person”, an argument long and damagingly used to try to convince homosexual people that they are, in fact, lovelorn heterosexuals.

One interviewee called a local gay switchboard, assuming that she would be met with understanding and acceptance from a group who, for decades, was told their sexuality was either immoral or illegal. She listened with incredulity as the person who answered the phone told her “asexuality doesn’t exist”.

Unlike celibacy, which is a choice, often sanctified with a vow, and unlike sexual dysfunction, which is often treatable, asexuality is in fact innate and immovable. Asexual people are not broken or defective. “It isn’t celibacy,” says Dore. “It isn’t sex negativity. It isn’t a choice not to have sex. All these do apply to some asexuals – and to some non-asexuals for that matter – but not to all.”

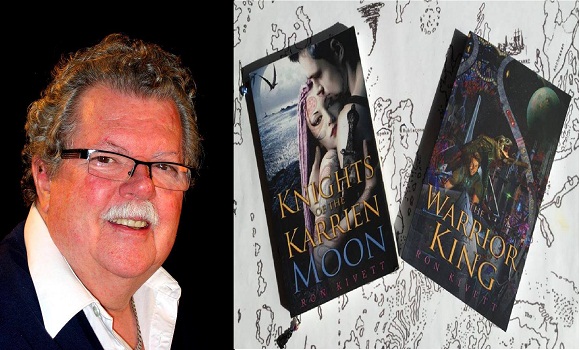

Bogaert, a professor of health Sciences and psychology at Brock University, has continued to dedicate his career to the study of asexuality. His book, Understanding Asexuality, the first of its kind, was published in 2012. He maintains, however, that our understanding is limited, and that it’s an area that demands further study. “More research needs to be done on the origins of asexuality,” he says. “There are studies suggesting that asexuality is affected by early biological factors such genetics, prenatal hormones affecting early brain development. Just like other sexual orientations asexuality likely has an early biological origin, or at least an early biological predisposition.”

One of the assumptions around asexuality is that the lack of sexual libido could be related to a hormonal deficiency. This can lead to the idea that an asexual person’s lack of desire extends beyond the realm of sexuality and, like a testosterone deficiency, leads to apathy in other areas of life. “I think we need to leave open the possibility that some asexual people have atypical circulating hormones, but there is not much evidence that this is generally the case for most asexual people,” says Bogaert. “Besides, some asexual people may still have some form of libido – but it just isn’t connected to others.”

Dore agrees that there is huge variation. “Asexuality is very much not a binary state,” he says. “There’s a whole spectrum. Someone might identify as grey-asexual or grey-A if they have lower sexual attraction than most people, but they can experience it sometimes.” There are also different romantic orientations, he says. An asexual person can be heteroromantic (falling in love with someone of the opposite sex), homoromantic (feeling love for someone of the same sex), biromantic (experiencing love for both sexes) or aromantic (craving love and intimacy from no one), to name a few. Some may enjoy non-sexual forms of physical intimacy – like cuddling – while others may find it disturbing.

To illustrate the range of experiences under the asexuality banner, a study carried out by The Asexual Visibility and Education Network (Aven), a support group founded in 2001 in San Francisco, found that 70% of asexual people said they were virgins; 11% of asexual people said they are not virgins but are currently sexually inactive;7% of asexual people said they are sexually active; 17% of asexual people said they were ‘completely repulsed’ by sex. Another 38% said they were ‘somewhat repulsed’ by sex, 27% said they were indifferent about sex, but 4%, perhaps rather confusingly, said they enjoy having sex.

Regardless of the difficulties involved in understanding such a complex and multifaceted group, Bogaert maintains that the work benefits all areas of sexual study. “By understanding asexuality better, we understand sexuality better,” he says. “It is important on a number of levels.”

It’s telling that the Frequently Asked Questions section of Aven’s website includes the rather mournful: ‘Will I always be lonely?’

Despite his eagerness to study asexual people, Bogaert remains acutely aware of the human challenges involved in living as an asexual person. “The biggest question facing asexual people is how to live in a world that is very sexualized,” he says. “They may face discrimination, or at least some level of disconnection, from the sexualized world. They may also face difficulty with finding romantic partners, as some asexual people are still romantic and want a love bond with another even if they are not sexual.”

It’s telling that the Frequently Asked Questions section of Aven’s website includes the rather mournful: “Will I always be lonely?”

In 2009 Doré joined Aven after he saw that some students from his university were members and wanted to meet them. “Before that, I just tended to avoid the topic of sex and relationships,” he says. That changed after Dore realised the importance of visibility. “If we aren’t talking about asexualtiy then people will assume it doesn’t exist or that there is something wrong with them,” he says.

The following year, when Dore went on a pride march for the first time in London, he mentioned to his parents that he was asexual. “I think it made a lot of things make sense for them,” he says, “perhaps for the first time.” Two years later Dore helped to organise the first worldwide conference on asexuality in London.

Aven has grown steadily during the past decade from 391 members in 2003 to 82,979 this year. Activism, too, appears to be on the increase. Many campus pride groups now actively include asexuality. There remains a lack of good data when it comes to true numbers, however. Clarity may be imminent. The Office of National Statistics is currently considering including listing ‘asexual’ as an option for sexual orientation in its list of questions for the 2021 UK census.

“To the asexual community, the possibility of inclusion as an option would be of indescribable importance,” says Dore. “For years, people have debated the question of prevalence, and we have very few hard facts to go on. Bogaert’s 1% figure has lots of disclaimers attached, and the actual figure is generally thought to be higher. The UK census would provide by far our biggest dataset. It would put asexuality on the map.”

Beyond prevalence, for Dore and others like him, the key is to combat the idea that asexual people are some how less rounded or fulfilled than others. “Some may feel we’re missing out on something great, but there’s always other activities to take their place,” says Dore.

“For most of us, it’s just one of our characteristics. It’s not an obsession.”

‘I have never felt sexual desire’